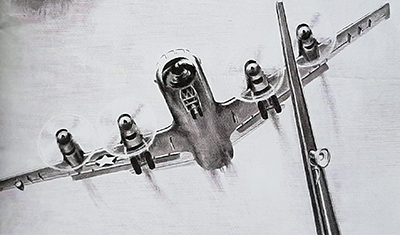

Missed Approach - 1965

From the Article "Missed Approach" in Approach Magazine

Submitted by: John Covert (who was aboard the flight)

Patrol flight crews are among many units in today’s Navy that are frequently called upon to put in exceptionally long working days. An eight-to-ten hour patrol usually requires one-to-two hours of briefing and preflight before takeoff and the same amount of time for postflight and debriefing after landing. Any way you cut it, a very long working day, approaching 15 hours, is the result. Strange as it may seem, patrol crews occasionally become involved in marathons of 24 hours or more, usually spending the last 10 or 12 hours of this period in flight!

way you cut it, a very long working day, approaching 15 hours, is the result. Strange as it may seem, patrol crews occasionally become involved in marathons of 24 hours or more, usually spending the last 10 or 12 hours of this period in flight!

Situations like this may develop somewhat as follows:

A crew reports to the squadron area at 0800 to begin preparations for assuming the Ready Alert at 1000. After checking out the aircraft and getting an OpCon briefing, everything is set. Now its just a question of waiting out the 24-hour watch.

During normal working hours, the crew will probably remain in the squadron area, working at their regular ground jobs. However, they may secure to on-station quarters earlier than usual … say around 1500. A few may be able to take naps at this time of day, but most of the crew, not being tired or sleepy, will probably sit around playing cards, reading or watching TV. The evening meal consumes an hour or so and then it’s back to more of the same … unless there is a good flick at the station theater. By 2100, it’s time to start thinking about hitting the sack … and then it happens.

The plane commander receives a call to launch the Ready Alert!

A short time later the P-3 is airborne, enroute to the contact area. Around midnight it arrives on station. Now the crew is starting its workday in earnest … about 16 hours after coming on duty. Three hours later, a message arrives requesting the P-3 to remain on station as long as possible. Upon receiving this, the pilot sets up two-engine operation, computes his off-station time, and transmits it to OpCon.

After what seems like an eternity, the black horizon begins to lighten faintly in the east as dawn approaches. A short time later, the first rays of sunlight begin beaming into the cockpit, further irritating eyes that are already red and burning from the effects of fatigue and staring for hours on end at lighted instrument panels.

The arrival of dawn brings with it an almost irresistible longing for sleep … regardless of the circumstances. Off-station time finally arrives, and the P-3 begins climbing out for the trip home. The weather forecast for ETA looks good … “Improving rapidly, forecast high scattered by 0900, visibility 10 miles.” At least they can look forward to a no-sweat approach and landing.

Shortly after arriving over home base, the plane commander receives a special weather observation. The station is still blanketed by fog with visibility at ½ mile. Precision approach minimums for the landing runway are 100 feet and ¼ mile.

Then GCA establishes radar contact and the approach begins. The pilot and copilot have been awake now for about 27 hours and in the air for almost half this period. The stage is set … for most anything.

For a closer look at what transpired in the next few minutes, let’s examine the pilot’s statement.

“The radar altimeter was set at 100 feet. After several vectors by GCA I commenced the final approach five miles out from the runway. During the approach everything was normal. My speed throughout was 130-140 knots. On final, GCA said ‘Take a wave off.’

“At this time, I leveled the wings and added power, then called for Max Power. With Max Power on I felt the port side of the aircraft hit something and felt a port yaw and vibration. I looked out the window and noted the No. 1 engine vibrating and called, ‘Feather No. 1!’ The flight engineer quickly feathered this engine with the emergency shutdown handle. I observed the pressure altitude to be 200 feet at this time and the aircraft was climbing. During the entire approach I did not see the field or the obstruction I hit. I was on instruments throughout.

“I raised the gear just before we broke out on top of the 600-foot cloud layer. The No. 1 engine was fully feathered and the vibration had ceased. We left the flaps at the takeoff and approach position where they had been throughout the approach.”

The copilot was looking outside, trying to spot the runway as the aircraft approached minimums. Here is his account of those few seconds just before and after the aircraft struck the fog-shrouded object.

“As we approached ceiling minimums, we were slightly above glide path. We set up a fairly good sink rate … in the neighborhood of 12-1500 feet per minute. As we approached minimums, I called, ‘Minimums.’ Noticing the red warning light on my radar altimeter come on at practically the same instant, I said ‘Minimums’ twice more. At this time, GCA called ‘Take a wave off centerline too far right.’

“I was now looking into the fog, attempting to see the field. I saw two vertical columns in the fog at about this time. It was apparent that we were going to strike these columns and I grabbed the yoke with both hands and pulled up and to the right. The port side of the aircraft struck these columns and a violent vibration ensued. I saw that the aircraft, nevertheless, was climbing and airspeed was normal. To the best of my recollection the pilot had initiated wave off power just before we hit the columns.”

On the way to an alternate field, the pilot tested the aircraft at various speeds and configurations. The remainder of the flight was routine.

Examination of the GCA tape at home base revealed that the P-3 was on course and on glide path at one mile from touchdown. About 10 seconds later, GCA reported “Going above, now slightly above, rising.” The pilot responded by reducing power, but the resulting rate then became excessive … about 12-1500 feet per minute. Four seconds later GCA waved off the aircraft because it was drifting too far left of the centerline.

Simultaneous with the instructions to wave off, the low level warning light (set for 100 feet) on the copilot’s radar altimeter came ON. His pressure altimeter also indicated 100 feet at the time. Response to the wave off instruction was reasonably prompt. Power was applied to level off and then climb out in accordance with missed approach procedure.

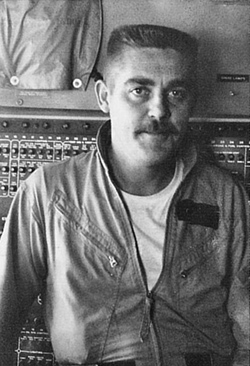

Initial power was 1400 hp according to the flight engineer. Had the rate of descent been close to 500 feet per minute at the time, this power application would probably have been sufficient for level-off, but the  P-3 was descending at at least twice this rate under instrument conditions with a fatigued pilot at the controls. (Photo to the right and above is of the I-beam obstruction)

P-3 was descending at at least twice this rate under instrument conditions with a fatigued pilot at the controls. (Photo to the right and above is of the I-beam obstruction)

Some two to four seconds after the initial power application, the pilot called for max power and began a pull-up. Impact with the I-beam an instant later provided an uncontestable indication that the aircraft was indeed well below the glide path. A second or two after impact, GCA called “Pull up, climb straight ahead to 1500 feet!”

During the investigation, it was determined that the 43-foot I-beam struck by the P-3 was attached to a floating dry dock that was temporarily moored at a pier on the perimeter of the air station. The exact position of the beam was 1070 feet from the approach end of the runway and 1570 feet from the normal touchdown point. This location put it within 40 feet of the ¼ mile visibility minimum and 380 feet to the left of the extended approach centerline. It penetrated 16.6 feet into the 50/1 approach slope.

The board felt that the pilot erred in not initially applying sufficient power to immediately establish a positive rate of climb when waving off. “An aircraft cannot descend on the glide slope to minimum altitude,” it commented, “and then level off immediately, without going below due to the inertia of the mass.” As a supplement to the normal GCA transmission “Approaching minimums,” the board recommended a procedure for NATOPS whereby the copilot would call out “Approaching minimums” or “100 above minimums” during the approach.

The following strong contributing factors were present in this incident, according to the board:

• Fatigue and impaired judgment caused by lack of sleep.

• The location in the approach zone to the runway of an unauthorized obstruction.

A program of continuing review of instrument approach zones was recommended “to insure that … objects do not conflict with the Criteria for a Standard Instrument Approach.”

Perhaps the GCA outside observer’s remark provides the most fitting conclusion to this story. Upon seeing the P-3 sweep low over the floating dry dock and then merge back into the fog, he exclaimed excitedly to the men in the GCA trailer, “Holy mackerel, fellers, that was close!”

[WebMaster’s note: This story was provided by John Covert as it appeared in the July 1965 issue of Approach Magazine. See John’s comments regarding this flight that he provided to us via a Pelican Post "Hey Jack" Letter September 2021 edition]

Hey Jack!

I am not sure that many alumni are aware of a very close call my crew (3) had late in ‘64 or early ‘65.’ Our crew was on a GCA after a 28-hour wake cycle, we were transiting a thin layer of fog about 60’ above the deck coming over the St. John’s, we strayed and the #1 prop struck a vertical I-beam on a barge anchored along the shore; part of one blade, the bottom of the nacelle and a chunk of the flap were all involved. The event was written up in Approach magazine, I can send you a copy of the article if you would like to employ it for some purpose. Dick Gray was in the middle seat; it was a memorable day.

Note. John then added the following detail:

The experience was chilling. I was seated in the radio compartment looking out with one eye. Everything happened in a flash. I felt the power surge and saw the I-beam and barge … there may have been men standing on it. The plane banked hard to starboard - #1 undulating violently and I heard loud voices in the cockpit. We quickly ascended through the fog and leveled off VFR while everyone regained composure.

PPC LCDR Jerry Jones advised Center that we weren’t landing anywhere that wasn’t VFR. We climbed to about 5K feet and put on our parachute harnesses and hardhats while determining where to land. We eventually settled on Warner-Robins in GA. The rest of the flight was uneventful. Chief Gray, our FE (then AD1) (pictured left) says that LT Fussell’s (2P) quick reflex to banked starboard saved us.

Bill Fussell was the most skilled Naval Aviator I ever flew with. He was somewhat unorthodox and sometimes pushed the officer conduct envelope. Gray and I could tell some great tales about him, but most wouldn’t serve well in the Pelican Post! Sadly he was killed a few months later in the crash of a civilian PT-22 owned by the Jax Navy Flying Club where he and I were both members. He was being checked out in the PT by one of the instructors. Their engine died at a couple hundred feet on climb out. They had no options but to go down in dense palmettos. Both five-point harnesses tore loose from the airframe and neither pilot survived. Bill left a wife and four little kids. I’ve often wished that I could meet those kids and tell them some stories about their dad.

Navy 151367 also took a piece of prop shrapnel through the fuselage and into the HF radio about 24” in front of my face. A small square patch was riveted over the hole. 151367 ended its service about 25 years later at one of the Icelandic Air Stations where it served as a station transport. Chief Gray obtained some pictures of the demolition and sent them my way – you could still see the small patch on the mangled fuselage!

John Covert

Send questions, comments or suggestions regarding this website to: vp45assoc@vp45association.org

Copyright © 2005 PATRON FOUR FIVE ASSOCIATION